Great Love of the Great Doctor: Zhang Xingru’s Philosophy of Philanthropy (IV)

【专栏】| Conlumists >微公益 | MicroCharity

By Yibai, Jointing.Media, in Shanghai, 2011-01-10

Success Lies In People,

Letting More People See Themselves Is Also A Kind Of Public Welfare.

“We believe that people participating in GMX is the greatest support.Any problem that can be solved with money is not a big problem.”

——Zhang Xingru

“It’s not just brightness, it’s hope.”

“A little girl in Tibet went blind because of her inverted eyelashes. The locals didn’t know it could be treated and believed that seeing a doctor wouldn’t help. But we went there and helped some people regain their sight, so that they would know this disease can be cured,” said a member of the GMX team.

A certain issue of the BiMBA alumni magazine featured the “GMX 2009″ as its cover story. Volunteer Liu Sizhuang, who participated in this event, wrote an article for the same issue:

“When patients rush in for treatment regardless of obstacles, when they walk unsteadily in and out of the ward, when they receive medication with gratitude in dialects we cannot understand despite being unable to undergo surgery, I feel that what they see is not only brightness, but also hope. If it’s not their turn this time, there will be next time, and as one problem is solved, other problems are not far from being resolved.”

Zhang Xingru hopes to achieve excellent results for cataract patients with the best doctors, equipment, and materials. He said, “Some people suggest buying cheaper materials to treat more patients, but our philosophy is that patients in remote and impoverished areas need to use the ‘best’. They do not have a second chance, and this opportunity is not only for themselves but also for the hope of others – if other patients see them being cured, they will have hope of being cured as well. If it is done poorly, others will think ‘oh, it’s still like this’. This will erase the hope of others.”

It is understood that GMX selects imported international brands of high-quality folding intraocular lens, and adopts the most advanced phacoemulsification cataract extraction intraocular lens implantation. The doctors who participate in GMX are experienced chief physicians and professor experts.

Activity is contagious

Most of volunteers of GMX are middle and senior managers and decision makers in enterprises, and Zhang Xingru believes that this “donation + experience” model can cultivate a sense of social responsibility in the management of enterprises participating in GMX. “There are a lot of things that you can’t feel until you see them. We feel that being there is the biggest support for GMX. Problems that can be solved with money are not big problems,” he said.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, a famous American philosopher, said that Activity is contagious. The social value orientation of an enterprise is mainly determined by the decision-makers and managers, and Zhang Xingru chooses to influence them, so that more people can see and feel, and then inspire them to act. He believes that entrepreneurs should care more about their employees and customers than shareholders, and fulfil their corporate social responsibility.

“We are not against eating delicacies, [not] asking [entrepreneurs] to donate all this money… There are a lot of upper classes who don’t see the real bottom of society. Many Tibetans are still hungry and barefoot, but many of them do not want money. How can we help them? When entrepreneurs saw that many people were living in extreme poverty, it was a big shock to them. Our model is better suited to our national conditions. (Doing charity for the public good in this way) is easier, comes from the heart, and is a combination of charity and public good.”

Zhang Xingru and the members of GMX often talk about GMX in their respective circles and talk about their personal feelings of participating in GMX, so the publicity of it is also spread from the dinner table.

“To live, one must have a little pursuit. To be able to do something that interests you and is beneficial to others, without hurting others, is also a pursuit. People are sometimes lonely, fickle or calm. There are not many days when man is truly peaceful and happy. But one thing ignited his hope-GMX is only once a year, but many people concerned. Caring is actually kindling people’s good hearts.”

Zhang Xingru, turned 50, admitted that GMX has taken up a lot of his free time. At first, his family was puzzled as to why he was “obsessed” with this nameless, unprofitable and thankless activity. But now his family, colleagues and leaders understand him very well.

“They think this thing is really effective. Besides, it’s not about time but what you do. For example, if you go to play mahjong, your family will be unhappy. But if you do public service and charity, your family will support you. Do valuable things to guide the family, infect them. Let them feel the value of doing public welfare.”

For businesses to see, for doctors to see, for patients to see, for people who read about them to see.Being seen bring hope. GMX care more about one’s own strength, and doing well is a social improvement.

(To be continued)

Translated by MirrorChat and Youdao Translate

Edited by Wind

Yifan Ding also contributed to this article.

Ralated:

Great Love of the Great Doctor (Ⅲ)

Great Love of the Great Doctor (Ⅱ)

Great Love of the Great Doctor (Ⅰ)

Great Love of the Great Doctor: Zhang Xingru’s Philosophy of Philanthropy (Ⅲ)

【专栏】| Conlumists >微公益 | MicroCharity

By Yibai, Jointing.Media, in Shanghai, 2010-12-16

Governing by doing nothing that goes against nature

“No organization, but with discipline”

We will not establish a foundation. Once established, it requires dedicated personnel to manage operations, which increases costs and consumes many social resources…We all work on GMX in our spare time, and no one is full-time. Moreover, all core members are all fluid. When one event is over, that’s it (a collective decision to do it next year). We are “unorganized but disciplined” — unorganized, unrestrained.

——Zhang Xingru

The first GMX in 2006 was initiated by Zhang Xingru, Yang Yongxiao, Ms. Jinglian, and Xu Yan. Many people shed tears in Zuoqin Township. Zhang Xingru said that at the time, GMX team encountered a young child in the snow. His shoes were worn out and his toes were rotten from the cold. When asked why he didn’t wear a better pair of shoes, the child answered:”No money for them.” It was the first time for all of us in Xinjiang, almost no one didn’t shed tears.

“The harsh living conditions faced by our comrades in the Tibetan region that we witnessed with our own eyes have left the members of the GMX team heartbroken. The happiness of those who regain their sight and the hope of a new start provide the team members with a sense of purpose. However, merely relying on emotions is not enough.”

Not Being a Foundation, Loose but not Dispersed

After the trip to Zuoqin, the members of GMX reflected and decided to continue the project long-term, creating a four-stop plan: foot of Tian Shan Mountains, old revolutionary base areas, Mongolian grasslands, and Yunnan frontier. This led to the GMX of Qinghe in Xinjiang in 2008, the GMX of Gannan in 2009, and the GMX of Grassland in 2010. With the initial plan nearing completion, they will plan six more stops for the future.

Since GMX is to be a long-term work, why not set up a special foundation? Zhang Xingru answered:” We will not establish a foundation. Once established, it requires dedicated personnel to manage operations, which increases costs and consumes many social resources. Some people have calculated that when you donate 10 yuan, only 3 to 5 yuan may actually be used for the intended beneficiaries, with the rest being worn away in the process. We want a more convenient operation where funds can be directly utilized without going through more intermediate links.”

“We all work on GMX in our spare time, and no one is full-time. Moreover, all core members are all fluid. When one event is over, that’s it (a collective decision to do it next year).” Zhang Xingru said.

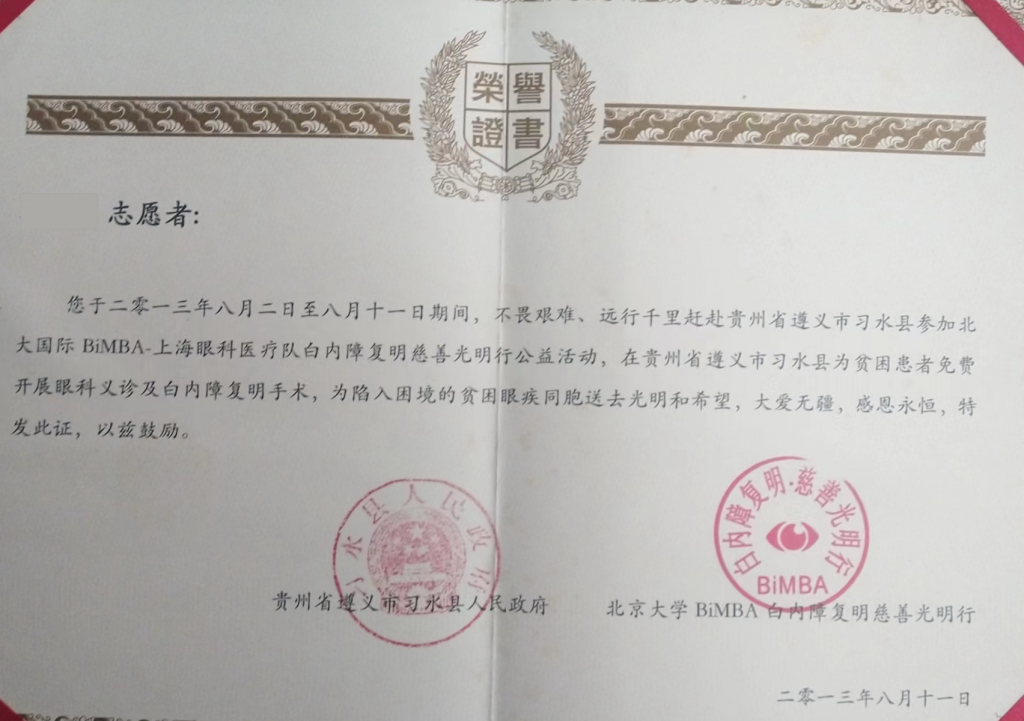

“I trust GMX a lot. Its operation is very transparent, and everyone can clearly see their position and value in the entire process,” said Liu Tao, manager of Bausch & Lomb China who has participated in GMX.

GMX is an intangible organizational entity with strict institutional procedures for action. They manage projects using a “budgeting before final accounting” approach, setting action goals, such as performing a certain number of cataract surgeries, before budgeting and fundraising. After the action is completed, they conduct accounting and publish expense lists to participating parties. The focus is on creating projects first and then procuring funds accordingly.

Who will manage the money? Faced with this sensitive question, Zhang Xingru bluntly said: “As the main organizer, the management of money must be handled by someone who has no connection with me.” It is understood that the money of last year’s GMX was managed by a volunteer named Qu Fei from a Shanghai company, which was one of the donors to last year’s GMX. A deputy director of the Shanghai Audit Bureau participated in GMX of this year as a volunteer and donor to “supervise” the financial transparency of the event.

Charity and social enterprises require a high degree of professionalism. Professionalism ensures the effectiveness of actions, which is related to the management capability of core members. GMX’s “strict system” mainly manifests in democratic decision-making and personnel selection; “transparency” is reflected in fundraising and the use of funds and materials, with the separation of operations and decisions. The supervisory mechanism plays an important role.

As Zhang Xingru pointed out, GMX does not have a formal organizational structure, but still operates with a sense of order and adherence to rules or guidelines.

Before Managing the Project, Manage the People First

Every year after the Spring Festival, GMX initiates project preparation and decide the departure time. The selection process for medical volunteers with fixed schedules takes priority, followed by enterprise volunteers. Due to variations in enterprise volunteer availability, the final list is confirmed only two weeks before departure. The roster is not changed once it is confirmed, but substitutes are assigned to each position.

The principle for GMX to select team members every year is to blend old and new members equally. Old members are familiar with the environment and work processes, and can guide new members to ensure medical accuracy. “In the past, when the scale was small, we could manage every aspect. But now that the scale has grown, it’s impossible to manage every aspect. And only after updating the team can it last. People’s passion is limited. Expanding access to opportunities can allow more people to showcase their kindness.” Zhang Xingru said.

There are many doctors applying to participate in GMX, but GMX has its own selection criteria. “We need to have a complete understanding of this doctor, otherwise the marginal cost will be very high. If you don’t understand his surgical skills, should he work as a doctor or as a volunteer or assistant? If he has a high reputation but poor actual ability, who will be responsible if something goes wrong?” As the captain of GMX, Zhang Xingru will also allocate team members according to the project, such as the ratio of new and old team members, the industry background of team members, and the resources available to each member.

“In 2008, GXM faced difficulties in medical equipment transportation, and Zhang Xingru pondered, ‘Next time we must bring in a team member with an aviation company background.’ In 2009, Ye Shenglan, a volunteer from Eastern Airlines joined the GXM team. He advocated for expanding the range of industries represented in the team and encouraging people from all professions to participate.”

The analysis of past data shows that the most economical and safest team structure is to limit the number of doctors and volunteers to 45 or less.There are now more than 200 potential volunteers.

Quality Control:Training and Backup

Each position at GMX has a job description. Volunteers are assigned to different teams based on their personal interests and expertise, and receive specialized training before deployment. “Volunteers must be trained. These volunteers who hold high positions in companies or units will be doing very basic work in GMX, such as simply assisting patients and helping doctors prepare for surgery,” Zhang Xingru said.

Hu Dayuan, a professor at Peking University, volunteered in the GMX in 2009, distributing eye drops to patients. In 2010, he was “promoted” to the ward and responsible for preoperative eye cleansing for patients. And Liu Chang, daughter of New Hope Group Chairman Liu Yonghao, was responsible for assisting patients.

Volunteers assisted doctors throughout the operation by registering patients, checking their vision, arranging patients, sterilizing, removing gauze, and distributing medicine. These auxiliary medical tasks do not require a long time of training to reach the standard. However, organizing and coordinating the work requires more management skills. Zhang Xingru’s approach is to fully authorize volunteers once they are assigned to a position, supervise them at any time, track progress, and prepare contingency plans.

“The equipment we move over each year is worth millions, for example, equipment that has been borrowed but malfunctions. There is always a contingency plan in place for critical positions.”

“For timing milestones and material gathering, it’s important to have a buffer of extra time and space. However, there are few things that need remedying because the members of GMX have strong sense of responsibility and execution ability.”

In usual circumstances, corporate executives and decision-makers who hold high positions are accustomed to being commanders. However, in GMX, they inevitably express their own opinions, especially since the company has donated money as a sponsor. Zhang Xingru said that this phenomenon did exist at the beginning, but later everyone reached a consensus on speaking rights: corporate volunteers leveraged their strengths to make suggestions and share management experience on project operations, while medical professionals had the final say on professional matters.

Although doctors and corporate volunteers have their respective roles, the overall direction of action is decided collectively. After each GMX ends, the members will hold a summary meeting to share their experiences and feelings, take turns to criticize, praise, and suggest. The main idea is “What should we do at the next stop? Where should we prepare to go?” The result of the meeting is always “keep moving forward.” Then everyone draws a circle to determine the general direction and confirms the details in specific operations.

“GMX is not a personal matter, it is a collective matter. Team communication and integration are not easy, I want to be inclusive of others,” said Zhang Xingru. He has always wanted to reduce his personal influence on GMX.

Most grassroots and spontaneous public welfare actions rely on the founder’s own influence and network to build a platform. Without a founder who possesses both appeal and inclusiveness, how can resources from different fields and partners with diverse personalities be gathered to accomplish the same vision?

(To be continued)

Translated by MirrorChat and Youdao Translate

Edited by Wind

Yifan Ding also contributed to this article.

Ralated:

Great Love of the Great Doctor: Zhang Xingru’s Philosophy of Philanthropy (Ⅱ)

【专栏】| Conlumists >微公益 | MicroCharity

By Yibai, Jointing.Media, in Shanghai, 2010-11-26

Steady and long,

knock open the door of kindness

“The cultivation and release of love is a process. And human kindness is not always present. Human nature has a selfish side and a kind side. We need to knock on the door of kindness and let love break free. Let there be more light and less darkness.”

——Zhang Xingru

Money Is Not a Problem?No!

It is understood that the cost of a GMX activity is about two to three hundred thousand yuan, including the freight of medical equipment needed for surgery and the cost of medical supplies. An enterprise once wanted to donate ten thousand yuan to GMX, but was persuaded to lower the amount. A foundation also proposed that this project aligned with their funding direction and offered a fixed budget, but GMX declined the offer.

“If one enterprise donates to the whole campaign, other enterprises won’t have a chance to express their kindness. If more people participate in each campaign, social value is greater. However, if the foundation provides full funding, it blocks the way for volunteers and enterprises to donate money. If they doesn’t donate money, they won’t go.” Zhang Xingru explained.

He added another layer of social significance to GMX, namely, corporate social responsibility(CSR)enlightenment action. “The enterprises not only need to donate money but also need to put in effort – actively participate in the activities and express their love directly through personal experience.”

In his opinion, the current public welfare system in China is not yet perfect, and the donation by enterprises and individuals has not been put into practical use. Some Chinese people prefer to burn incense in temples rather than donate ten yuan to poor and out-of-school children. In addition, with more and more negative reports about some NGOs, people’s enthusiasm for public welfare is dampened.This is like a blocked water source that will not be demonstrated in the future, and the enthusiasm will be wasted.

“The cultivation and release of kindness is a process. It’s not possible to have a very high level of kindness all at once. Kindness is not always present, as human nature has two sides: selfish and kind. We need to knock on the door of kindness and let our hearts be unleashed. Let there be more bright and less dark.”

To Believe That A Single Spark Can Start A Prairie Fire

Zhang Xingru’s philanthropic beliefs are related to his personal growth experience. In the late 1970s, he was a college student and first came into contact with “philanthropy”. In his impression, companies did some philanthropic activities in order to increase their visibility. For example, the corporate sponsorship banners during the “Iron Hammer” era of women’s volleyball matches. After becoming a doctor, he started to participate in free clinics organized by others. Along with participating in multiple similar events, he began to contemplate if he could establish a charitable initiative with innovative value that aligns with China’s national conditions and can be replicated. He envisions that doctors from all disciplines can also go to impoverished areas on the periphery to provide free medical services with entrepreneur funding.

“We are currently exploring this path. If some person integrates some resources, they can all participate in charity and public welfare work, which can be big or small. For example, a dentist and an entrepreneur could team up to provide dental care and education for people with poor oral health in remote areas. The entrepreneur has the funds and compassion, while the dentist has the skills. By combining their expertise and resources, they can accomplish concrete results.

“Small sparks can start a prairie fire.” Zhang Xingru hopes to popularize the GMX model. Each discipline can form a medical team and join forces with some entrepreneurs or philanthropists who have both compassion and financial resources to form a volunteer team and provide medical services in remote areas for the elderly and children in need.

“We are definitely going to very remote and impoverished areas, and they are mostly minority areas,” Zhang Xingru repeatedly emphasized their direction. He explained, “Large (medical charity) organizations generally find it difficult to reach such places. They have to locate management teams and contact local governments to penetrate these areas, which takes a lot of effort, and may not necessarily achieve excellent results in the end.”

Sometimes kindness can also lead to bad results. If mistakes are made, it will hurt many people’s hearts and erase kindness. Kindness should be turned into good deeds, and good deeds must be done well. This requires the leaders of public welfare actions to not only have the ability but also wisdom.

The leaders of charity and public welfare activities need to stand taller, look further, and have a broader perspective. Actions speak louder than words, and perseverance is more important than temporary bursts of energy. Persistence is key, and this is also what Zhang Xingru persists in.

(To be continued)

Translated by MirrorChat and Youdao Translate

Edited by Wind

Yifan Ding also contributed to this article.

Ralated:

Great Love of the Great Doctor: Zhang Xingru’s Philosophy of Philanthropy (Ⅰ)

【专栏】| Conlumists >微公益 | MicroCharity

By Yibai, Jointing.Media, in Shanghai, 2010-08-28

From July 16th to 24th, 2010, the “Charity Brightness Tour” successfully completed its fourth stop – the “Prairie Brightness Tour.” Since its inception in 2006, more than four years have passed in silence. The team members of the Brightness Tour raised funds on their own and used their spare time and professional expertise to explore a new path of public welfare. What attracted them to this point? What is the significance and contribution of their practice to themselves and society? Professor Zhang Xingru, the initiator of the Brightness Tour and vice president of the affiliated Putuo Hospital of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, gave his first interview, sharing his insights on their practice of public welfare.

Study the nature of things,

Act according to one’s ability,

Find joy in doing public welfare

“Has donating money achieved the original intention of everyone participating in public welfare? It is easier to succeed by using one’s own skills and integrating social resources, and it is more valuable to oneself. Through one’s own labor, Brightness Action brings light to others, and this is the philosophy that we follow.”

——Zhang Xingru

First Brightness Action, 13 and 18

In January 2006, 13 people and 4 cars, carrying over 270 types of medical equipment, completed 18 eye surgeries on temporary operating tables made of local wooden boards at an altitude of over 4,000 meters on the snowy plateau. This was the first expedition of the Brightness Action(Cishan Guangming Xing, which means “bring light”), a philanthropy program that restores sight through cataract surgery (hereinafter referred to as “GMX”).

It sounds like the journey was quite an adventure, with the team of 13 medical professionals and volunteers traveling from various locations such as Beijing, Shanghai, and the United States to converge in Chengdu, Sichuan. They then embarked on a three-day journey by car, crossing the Dadu River, the Jinsha River, the Erlang Mountain, and the Zheduo Mountain, which is over 5,000 meters high, and approaching the 7,000-meter-high Que’er Mountain. Along the way, they encountered mudslides and heavy snowstorms, which must have been quite challenging. As the team leader, Zhang Xingru was understandably concerned about everyone’s safety, but they eventually arrived safely.

Looking back on this trip, Zhang Xingru still remembers it vividly. “Thirteen of us (ophthalmologists and volunteers) came from Beijing, Shanghai, the United States, and other places to converge in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. Then we took a car for more than three days. We crossed the Dadu River, the Jinsha River, the Erlang Mountain, and the Zheduo Mountain, which is over 5,000 meters high, and approached the Que’er Mountain, which is over 7,000 meters high. At that time, we also encountered mudslides and heavy snowstorms. I’m the leader of the medical team, with the doctors from our hospital, and very worried about everyone’s safety. We were jolted all the way and frightened, but we finally arrived safely.”

Zuoqin Township in Dege County, Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, is located at the junction of Tibet, Sichuan, and Qinghai provinces, at an altitude of over 4,000 meters. The intense ultraviolet radiation on the plateau in this Tibetan region has led to a high incidence of cataracts among the local population. GMX’s team members were mentally prepared for the difficult environment, but the medical conditions were still unexpected, so they had to redesign the surgical plan.

“We arrived after a four-month drought, and it rained heavily for a day and night. The locals said we brought a good rain after a long drought. But the heavy rain destroyed the hospital’s power system. The operation was delayed a day and carried out from morning until midnight without air conditioning in 40-degree temperatures. Sometimes the machines began to malfunction due to overheating. At that time, I just thought that as long as there was a rainproof house, it would be fine. We brought our own medical equipment and the bed was made of local wooden planks,” Zhang Xingru recalled.

The original plan was to perform 10 surgeries, but due to an increasing number of patients who came after hearing about it, GMX ended up completing 18 surgeries, including 7 local monks.

According to statistics, 108 Tibetan eye disease patients received free medical treatment, all 15 cataract surgeries and 3 ophthalmic surgeries were successful in the first GMX charity project. When they saw the patients open their eyes and see after the surgery, the GMX team members were moved to tears.

“We have also gained valuable experience in conducting cataract surgery under difficult conditions,” Zhang xinru said.

Happiness Driver

Zhang Xingru undertakes a lot of hospital management work as vice president of the hospital. Meanwhile he is the organizer and team core of GMX as co-founder. GMX project, once-a-year voluntary action, is a part-time job for him. Just organizing and coordinating would eat up three months of his spare time. He sacrificed a lot of time with his family. But his family not only supported him in running the project, but his children really wanted to be part of it in the end.

He said, “Although participating in such voluntary activities is very educational for her, I cannot let her go. If everyone brings their children, it will affect the seriousness of this action.” Voluntary action is not entertainment, it is a job, and a serious one at that. This is Zhang Xingru’s opinion.

Yin Jianhong, a volunteer who participated in GMX’s trip to Gannan in 2009, wrote in an internal publication of GMX that the hardest person is Dean Zhang Xingru. From planning to implementation, from medical services to logistics, he is meticulous and conscientious, a role model.

Talking about a lot of effort and dedication for voluntary action, Zhang Xingru believes that the greatest reward is happiness. He said that through such a platform of GMX, he has met like-minded friends from different fields, and everyone can see the joy brought by their small voluntary actions while practicing public welfare, and see the value of their actions.

Doctor Jiawancheng said: “As doctors, we often move others, but we don’t have many opportunities to be moved ourselves. However, GMX gave us the opportunity to be moved.”

As the old saying goes: A single hand cannot make a sound, one log cannot prop up a building. The main team members of GMX are aged 35-50, and they are the backbone of society and the pillars of their respective families. They reshape their social value through GMX. Every year, when the selection for GMX team members is approaching, people constantly ask Zhang Xingruo: “Dean Zhang, when are we going again this year?” GMX has become a spiritual sanctuary for many people. Being needed by others brings happiness.

Doing What We Can

“It’s very satisfying to do public welfare within one’s capability, and everyone is very happy doing it.” Zhang Xingruo said. Some wealthy people donated some money, others provided free labor, and those with specialized skills contribute their expertise. He advocates that it is more valuable for technically skilled people to contribute to public welfare by doing what they are best at.

“Did the donating money achieve its original intention? It is easier for us to be successful and valuable to ourselves by integrating the resources of society with our own skills. We bring light to others through our own work. We do it through this idea.”Zhang Xingruo said.

All equipment, consumables, patient diagnosis and surgical fees, as well as living expenses for each activity are self-funded by GMX members. Most of the funding comes from donations by volunteers, ie., students in Peking University’s EMBA program. Professional doctors are sourced from top-tier hospitals in Beijing and Shanghai.

Zhang Xingruo emphasize the importance of knowing your limitations and controlling the number of volunteers and surgeries per session. He said that although there are many patients and demands, we must also work within our limits to ensure the quality of surgery. Knowing what you cannot do is essential to focus on doing what you excel in. It’s not necessary to do things with great fanfare, rather, do them quietly and humbly.

Study the nature of things and act according to one’s ability, this is the tone Zhang Xingruo set for the GMX.

(To be continued)

Translated by MirrorChat and Youdao Translate

Edited by Wind

Yifan Ding also contributed to this article.

Ralated:

Great Love of the Great Doctor (Ⅱ)

Great Love of the Great Doctor (Ⅲ)

Great Love of the Great Doctor (IV)

Great Love of the Great Doctor (V)

Chen Ya:Decluttering is a Practice of Death

By Chen Ya, Jointing.Media, in Wuhan, 2023-04-05

Tulips in the yard (2023)

SQM, Jointing.Media

The documentary “Human: The World Within” has calculated the amount of resources consumed by an individual over their lifetime, revealing that each person will consume around 35 tons of food, generate 8.5 tons of food packaging waste, drink 146,000 gallons of water, use 4,239 rolls of toilet paper, wear 192 pairs of shoes, and use 46 sets of clothing. In addition, an individual will typically take around 7,163 showers, consuming hundreds of thousands of liters of water, along with 656 bars of soap, 198 bottles of shampoo, 272 bottles of body spray, 276 tubes of toothpaste, 78 toothbrushes, 411 skincare products, 35 tubes of hair gel, 37 bottles of perfume, 25 bottles of nail polish, and 21 tubes of lipstick. For women, this also includes the use of around 11,000 sanitary pads, as well as several bottles of sunscreen.

Is it truly necessary to consume as much as we do in order to survive? Lauren Singer, a 25-year-old Environmental Science graduate from New York University, has been living a “zero-waste lifestyle” since 2012. She maintains a vegan diet and refuses to utilize any plastic products, handcrafting nearly all of her daily necessities. Over the course of four years, , the only waste she has generated is contained within the following modest jar, which is a fraction of what most individuals produce in a single day.

Image source: from network

There’s a distinct class of goods defined as modern necessities, such as personal computers. The manufacturing process of a single computer requires a staggering 240 kilograms of fossil fuels, 22 kilograms of various chemicals, and 1.5 tons of water. The material consumed by a single computer, prior to leaving the factory, is equivalent to that used by an entire car. The disposal of discarded computers also presents a significant challenge. According to recent studies, the average person discards 40 tons of waste into landfills over the course of their lifetime.

Would a person who advocates for an environmentally-friendly lifestyle become an unscrupulous “shopping fanatic”? A human lifespan consists of approximately 30,000 days, during which time both time and money are precious resources. When one’s life comes to an end, possessions that are unable to be taken away become either cherished contributions passed on to future generations or items that are discarded or recycled.

Objects that were once in the possession of historical figures have a cultural and historical value that exceeds their material worth. Often referred to as “cultural relics,” examples of such objects include dragon robes and crowns. Their value lies in the cultural significance they carry, and not in the function they serve. Ordinary individuals, upon passing, tend to have their clothes either burned or donated. As for other items, the preference is to replace them with newer objects that have more practical use, unless they hold artistic or antique value that may appreciate over time. Unfortunately, nobody can predict how long these items will be retained by future generations. This becomes especially challenging in the core areas of first-tier cities where the price per square meter approaches 100,000 yuan, leaving little space to store “useless” objects. As time passes and successive generations come and go, the emotional significance that these objects once carried fade away, along with the physical form of both the objects and the descendants who once owned them.

What is death? Death is the concept of beings and things that have vanished, that we can no longer see or encounter again. Once the heart forgets, forgetting becomes tantamount to death. To this end, some say that “true death is when no one remembers anymore.” Therefore, in Chinese culture, individuals are encouraged to establish their moral principles and express their ideas prior to passing away. Looking at it from another perspective, the value of material possessions lies in the memories and time they carry. When we come across certain objects, they prompt us to think of the people associated with them and the times we shared. After all, such objects are merely triggers for memories and never the most crucial part of them.

There was once a report about a Chinese artist who curated an exhibition using objects cherished by his deceased mother. The vast number of items on display was astonishing. Undoubtedly, this type of personal exhibition holds practical significance as it presents a string of old objects that bear both the imprints of time and individual experiences. These objects tell the story of an ordinary Chinese woman’s life journey and reflect the changes of her times. Such exhibitions can prompt viewers to ponder the present and contemplate the future. However, has any journalist kept tabs on the aftermath of this exhibition? I suspect that, much like the human body, these objects will eventually revert to their basic particles after reaching the limits of their respective materials’ lifetimes, unless they are preserved and collected in a museum. Though each takes a different path, all lead to the same destination.

Some argue that consumption is not only a means of survival but also a way to fulfill psychological needs. “Buying, buying, buying” is seen as a reward for one’s hard work, a way to “treat oneself well.” However, in many cases, people’s consumerist beliefs are implanted subconsciously. In “Work, Consumerism, and the New Poor,” sociologist Zygmunt Bauman portrayed the situation in developed countries in the 1990s. In a consumer society, a “normal life” is one lived as a consumer, where one can choose from a variety of products and enjoy pleasant feelings and vivid experiences. For poor individuals in a consumer society, lacking the ability to live such a “normal life” means they are seen as failed, deficient, and inadequate consumers.

“The main demand placed on individuals by society is to participate as consumers, and first and foremost, to shape its members according to the requirements of the ‘consumer’ role, with the expectation that they have both the ability and willingness to consume.” (page 29) In other words, the focus of society has shifted from production to consumption, and the way people integrate into the social order and find their place in it has changed. At this point, “people must first become consumers before they can have any other special identities.” (page 33) While producers in society still exist, their significance and meaning have changed. In particular, in the consensus that “consumption leads the economic recovery,” economic growth is dependent not only on “national productivity” but also on the enthusiasm and vitality of consumers themselves. Corresponding to this change is the fact that stable, long-term careers with guarantees and certainty are no longer widely available, while permanent, secure, and predictable jobs are increasingly scarce. New jobs often have deadlines or are part-time, and the trendy concept of “flexible” employment represents a game of employment and dismissal with almost no rules. (page 34) Bauman’s observations were of the social landscape of the 1990s.

Due to a lack of personal consumption evaluation and tracking systems, combined with a general absence of self-awareness regarding the impact of individual behavior, people tend to overestimate their own consumption ability, leading to excess consumption and unnecessary accumulation of possessions. This tendency towards overconsumption leads to secondary waste and environmental pollution. According to various statistics, globally, at least 30% of food is wasted each year, with nearly 60% of resources being hoarded, around 2% of electricity being wasted, and industrial waste accounting for around 30-50% of total waste, and building waste accounting for about 30-50%. Studies have shown that if all stages of the food supply chain are considered when calculating waste, then the greenhouse gas emissions associated with food waste will account for approximately 8% to 10% of global total emissions.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP) 2021 Food Waste Index Report, an estimated 931 million tonnes of food was wasted worldwide in 2019, amounting to 17% of total global food available to consumers. The report notes that this amount of wasted food could fill 23 million 40-tonne trucks, which if placed end-to-end, would circle the Earth seven times. Furthermore, although food waste is typically seen as a problem only in high-income countries, this report finds that almost every country and region evaluated has food waste issues, with the severity not being dependent on income level.

The United Nations predicts that the world’s population will increase from 7.6 billion to 9.8 billion by 2050, making it difficult for food production to keep up with rapid population growth. In addition, around 3 billion people worldwide cannot afford a healthy diet. The world is now facing its most serious food crisis in 50 years. The population of people affected by food crises increased by the largest amount in almost four years in 2019, with a total of around 821 million people experiencing hunger, and the COVID-19 pandemic could cause an additional 130 million people to suffer from hunger. However, at the same time, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) 2019 report on world food security and nutrition, about one-third of the world’s food produced each year, a total of approximately 1.3 billion tonnes, is lost or wasted.

In the novel ”The Elegance of the Hedgehog,” Paloma uncovers a small secret kept by the apartment concierge, Honey. However, Honey’s unexpected passing prompts her to reexamine her outlook on life and death. This year’s Qingming Festival marks the first observance of the festival in China after three years of battling a pandemic, causing individuals to continually confront death during this period.

It is crucial to appreciate food, consume in moderation, and safeguard space for our fellow beings and other creatures. As one reaches middle age, changes in physical function may also bring about psychological changes. Adopting the lifestyle of disassociation can also become an expression of one’s attitude towards life. The human body is akin to a house, with a lifespan of seven to eight decades, accumulating possessions beyond our actual needs. Decluttering is, in essence, a death practice.

Author’s bio: Chen Ya, a person living in another world.

Translated by Google Translate

Edited by ChatGPT Next、Wind

Ralated:

Chen Ya | From ChatGPT to Creative Education

Billionaires Focusing on Greenland Island

【能源与环境】 | Energy & Environment

By Yibai, Jointing.Media, in Shanghai,2022-08-18

Recently, news about the record-breaking melting of glaciers in Greenland appeared in financial news. There are reports that the world’s top billionaires are going there for mining.

The acceleration of ice and snow melting in Greenland is caused not only by the global climate change but also by the capital warming up this natural “permafrost” and turning it into a hot market. On the west coast of Greenland, the wealthiest investors in the world are funding a massive mineral exploration project, hoping to find the crucial mineral that will power hundreds of millions of electric vehicles.

According to media reports, 30 geologists, geophysicists and other relevant personnel are currently stationed at the exploration site on the west coast of Greenland. These individuals are collecting soil samples, operating drones and helicopters equipped with signal transmitters, and analyzing data with the help of artificial intelligence, all in the hopes of accurately locating drilling sites as early as next summer. The project is a joint venture between US-based mineral exploration company Kobold Metals and British mining giant Raven Resources.

Greenland’s literal meaning in Danish is “green land” (Grønland), while the English translation “Greenland” can be interpreted as an “oasis.” This impression inevitably brings to mind the science fiction film Ready Player One, released in 2018. In the film, humans search for Easter eggs in a virtual world called “the Oasis,” hoping to take over and become the richest person in the real world, while in reality, the wealthy are searching for minerals in “Greenland.” The comparison is, amusingly, quite apt.

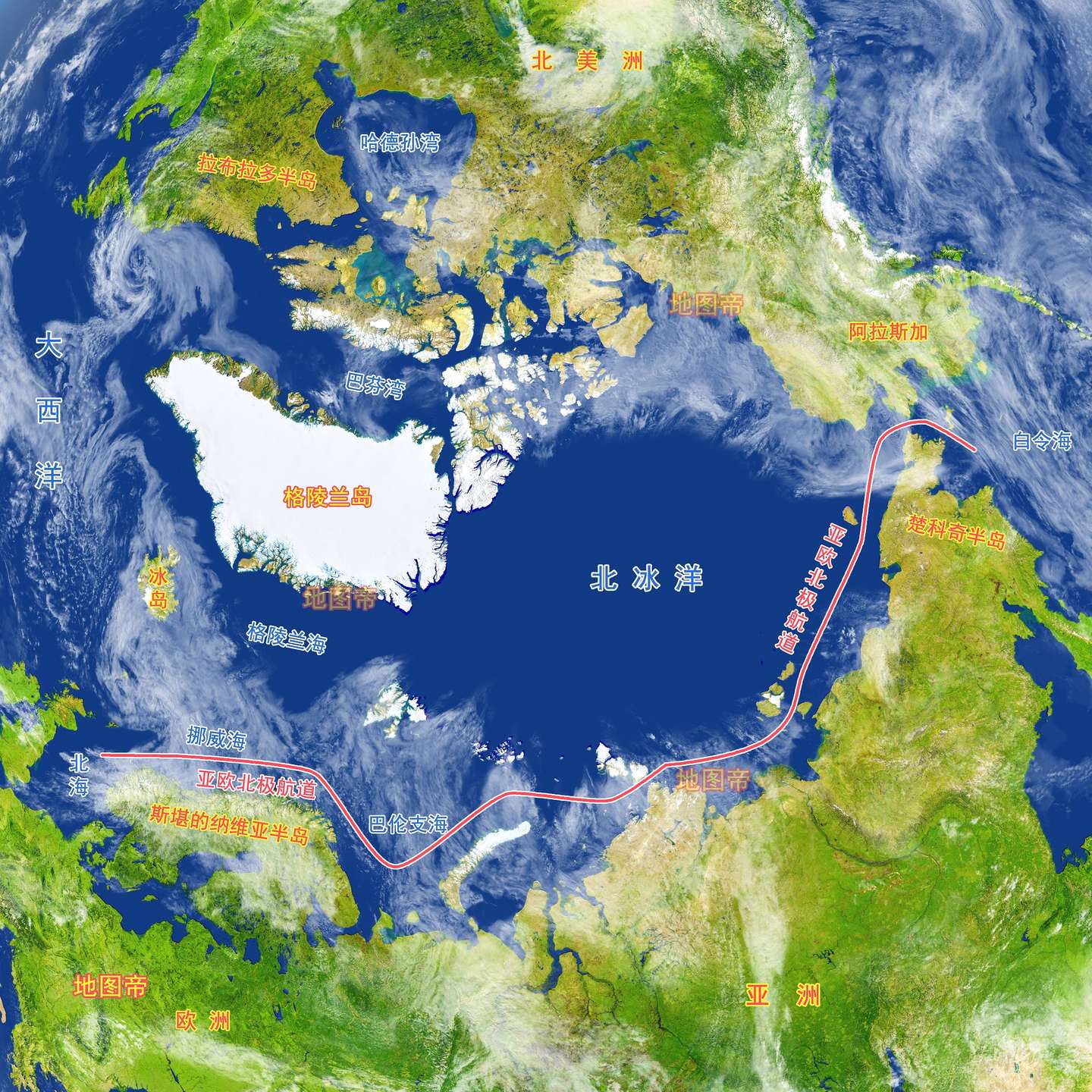

Glaciers Melting at an Accelerated Pace

According to data, the ice sheet of Greenland covers an area of 1.8 million square kilometers, second only to Antarctica’s ice sheet. The average thickness of its ice layer is about 2300 meters, and the average temperature is around minus 31 degrees Celsius. The melting of Greenland’s ice sheet began in the 1970s. Since 1980, the rate of loss of the Greenland ice sheet has increased by six times. The reasons for the accelerated melting of glaciers are two-fold: the rising temperature caused by global warming leads to more surface ice melting, and warm Atlantic seawater begins to erode the glaciers from below.

The period from 2011 to 2020 was the warmest decade on Earth since 1850. The global average temperature is 1.2℃ higher than the pre-industrial level (the average value from 1850 to 1900). The current sustained weather pattern hints at a peak in glacier melting.

In 2019, Greenland lost 532 billion tons of ice, a historic high and double the annual average since 2003.

On August 27, 2020, the largest ice shelf in the Arctic, the 79N glacier (also known as Spalte), located in northeast Greenland, broke apart, with a 110 square kilometer ice tongue breaking off and breaking into many icebergs that floated on the water’s surface.

In 2021, Greenland experienced the largest rainfall in 71 years, lasting for 9 hours. The ice sheet underwent two intense melting processes, and 8 billion tons of ice cover melted every day.

Between July 15th and 17th of this year, 6 billion tons of melted water flowed into the ocean from Greenland each day, and the amount of ice and snow melted in three days could fill 7.2 million standard Olympic swimming pools.

Glacier melting data has repeatedly broken records, leading many to believe that the countdown to the disappearance of the Greenland ice sheet has begun. Satellite data over the past 40 years has shown a significant reduction in glaciers on the island. Even if global warming were to stop now, the ice sheet will continue to shrink. A study published in Nature Communications Earth and Environment shows that Greenland’s glaciers have already crossed a critical point, where the amount of ice flowing into the ocean from glaciers exceeds the annual snowfall that replenishes the ice sheet.

A study published by Nature magazine at the end of 2019 showed that the Greenland ice sheet lost nearly 4 trillion tons of ice from 1992 to 2018, causing the global sea level to rise by about 10.6 millimeters. Additionally, a report released in October 2020 indicated that, based on high-carbon scenarios, the mass loss of Greenland’s glaciers during this century may exceed any period in the past 12,000 years, as shown by the establishment of cross-millennial, high-resolution simulations of the Greenland ice sheet.

Another concerning issue, in addition to the rise in sea levels, is that the melting water from Greenland is slowing down the Gulf Stream in the Gulf of Mexico. The Gulf Stream, or more precisely the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), brings warm water from the equator to the North Atlantic and cold water to the deep sea, and is the reason for the mild climate in Western Europe. Over the long term, sustained global warming could further weaken the AMOC through changes in the hydrological cycle, reduction of sea ice, and accelerated melting of the Greenland ice sheet.

In August 2018, researchers at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany reported in Nature magazine that since the mid-20th century, the strength of the AMOC has decreased by 15%. The weakening of the AMOC is believed to have had an impact on European weather, as seen in the record cold snap in the Atlantic in 2015, which was thought to have contributed to the European heatwave of that year. Model simulations further suggest that the weakening of the AMOC could become the primary cause of “future changes in summer atmospheric circulation over Western Europe,” possibly resulting in increased storms in Europe. The weakening of the AMOC is also associated with the rising sea levels above average on the East Coast of the US and the worsening drought in the Sahel region of Africa.

The search for “oases” is endless treasure hunting

Since its establishment five years ago, BEV has set up four risk investment funds with a total size of $2.2 billion (including one euro fund), invested in 112 projects worldwide, and exited 4 projects. A small portion of its funds has also supported some public welfare projects. BEV aims to double government investment in clean energy innovation within five years, promote private capital investment in excellent clean energy technology companies, and promote knowledge sharing in the clean energy field. Its official website displays the belief of the former world’s richest man in using technology to save humanity’s future.

Although it is not true that billionaires have actually formed a consortium to mine in the “oasis,” it is an undeniable fact that the desire for capital to control resources and the ever-growing thirst for them, just like the rich mineral resources in Greenland, exist. The warming of the earth has caused the melting of Arctic glaciers, and the Arctic Ocean route has drawn the attention of coastal countries. Everyone wants to gain an advantage in future national competition.

While most of the Arctic region is in the Arctic Ocean, a large part of it is under the sovereign jurisdiction of the Arctic states. The United States, Canada, and Russia have each authorized their respective secondary government agencies to govern Alaska, the northern territories of Canada, and Russia’s independent political entity in the Arctic region. The indigenous people of the Arctic have also been given different rights. Finland, Sweden, and Denmark are all members of the European Union, but Greenland decided not to participate in the European Economic Community at the time, so Greenland has extensive autonomy. Geographically, Greenland is an important military fortress.

Global warming has entered an accelerated stage, and since it is impossible to stop the melting of glaciers, resources that were originally preserved for future generations can be mined from the land that glaciers have retreated from, in order to seize market opportunities and gain more market share. “Capable of reaching the moon, and capturing fish in the deep sea,” this is why technology needs to continue to breakthrough (so there is the “Breakthrough Fund”?), and it is also one of the driving forces for continuous technological progress and sustained capital investment.

The degree to which resource extraction contributes to the accelerated melting of glaciers still needs to be observed and demonstrated by scientists through data, although data generally lags behind established facts. In addition to hoping that advanced technology can minimize environmental impacts as much as possible, what ordinary people can do may be to practice energy conservation and emission reduction in their daily lives.

The book “Limits to Growth,” first published in 1972, has long since pointed out that human development is not sustainable. Based on the data available then, the book concluded that the impact of the human ecological footprint had already exceeded the limit, the feedback loops of the ecosystem had fallen behind, and its self-recovery capacity had been severely damaged. If the current rate of resource consumption and population growth continues, the growth of the human economy and population will reach its limit in just a century or even less. The report calls for a transformation of the development model from unlimited growth to sustainable growth, and to keep growth within the limits that the Earth can sustain.

In 2008, Australian scholar Graham Turner published a paper titled “Comparing the Limits to Growth with Thirty Years of Reality,” which confirmed that the changes in industrial production, food production, and pollution in the past thirty years are in basic agreement with the predictions made in “Limits to Growth.”

The irreversible melting of glaciers has already passed the critical point. What about the fate of humanity?

Editor’s Note:

Only 3% of the water on Earth is freshwater, primarily in the form of glaciers. 0.036% of freshwater exists in lakes, rivers, and reservoirs, and 0.001% of freshwater exists in clouds or as water vapor. Nearly 90% of the Earth’s ice is in Antarctica, with the rest mainly in Greenland. If all of the ice in Antarctica were to melt, it would raise sea levels by 60 meters. However, even if all the water in the atmosphere were to turn into rain and fall evenly across the globe, it would only deepen the oceans by 2 centimeters.

The ocean is the true powerhouse of the Earth’s surface activity. In fact, meteorologists increasingly view the ocean and the atmosphere as a single system. The amount of heat delivered daily to Europe by the Gulf Stream is equivalent to 10 years of global coal production. This is why the winter climate in the UK and Ireland is relatively mild compared to Canada and Russia. However, water heats up very slowly, so even on the hottest of days, the water in lakes and swimming pools is still cool.

Seawater is not a homogeneous body. Differences in temperature, salinity, depth, and density among seawater in different regions have a great impact on the way heat is transferred through the ocean, which in turn affects the climate. The main carrier of heat transfer on Earth is known as thermohaline circulation. It originates from slow ocean currents in the deep ocean: surface seawater reaches Europe and increases in density, sinking to the bottom and slowly returning to the Southern Hemisphere. This batch of seawater reaches Antarctica and encounters the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, pushing it forward into the Pacific Ocean. This process is slow, with seawater taking 1,500 years to flow from the North Atlantic to the central Pacific. However, the amount of heat and water it transports is considerable, which has a significant impact on the climate.

Reference:

- https://www.sohu.com/a/576972403_121345914

- https://www.cas.cn/kj/202011/t20201123_4767728.shtml

- https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20210807A08VYS00

- https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/348913236

- https://www.cdstm.cn/gallery/hycx/qyzx/202010/t20201031_1036518.html

- https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/96802213

- https://www.marketscreener.com/quote/stock/BLUEJAY-MINING-PLC-15082161/news/Bluejay-Mining-KoBold-Metals-signs-US-15m-deal-to-earn-into-Disko-nickel-project-in-Greenland-36128015/

- https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/breakthr

- ough-energy-ventures

- https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/kobold-metals

- https://philanthropynewsdigest.org/news/breakthrough-energy-coalition-launches-1-billion-ventures-fund

- https://www.breakthroughenergy.org/

Translated by ChatGPT Next

Edited by Wind

Image Source:Ditudi、Pixabay

Ralated:

Chronicles of Fighting Against the Epidemic 2020:Spring Breeze and Wildfire,History Always Repeat Itself

“Time flies! It’s been three months already,” recalling the medical supply donation action that he participated in during the early days of the lockdown in Wuhan, Xiaoye couldn’t help but sigh at the ruthlessness of time. “To be honest, I don’t even remember what I was doing on Chinese New Year’s Eve anymore, because it was non-stop work around the clock during that time.”

“The most needed items during the Spring Festival were (protective) medical supplies, followed by logistics resources, and donations were actually the most abundant. I noticed this problem as soon as I joined the group. So, I first searched for intercity and international logistics resources through various channels to help alumni who had found sources of goods solve their logistics problems. After all, alumni have a certain level of trust and are easy to do background checks on, which is better than strangers met online,” Xiaoye said. He has 20 years of work experience and always likes to summarize his work habits. The group he mentioned refers to a WeChat group organized by a group of alumni to assist Wuhan hospitals. Xiaoye is one of the donors.

He said, ”The logistics experts who were finally confirmed were recommended by friends who knew and trusted them. I don’t trust resources recommended by people I don’t know or haven’t dealt with. It’s not just about being enthusiastic, it’s harder to spend money than to make money. To spend money well and get things done, you have to carefully choose your partners, and that’s always the case.”

If it were you, you would do the same

Actually, Xiaoye’s sense of crisis was not initially so strong. At first, he saw the same information online as most people. As more and more requests for help from hospitals and doctors were transmitted in the WeChat group, he began to donate money. “At first, it was just a donation following the crowd. I have been doing public welfare work in my spare time for more than ten years, and donating and participating in volunteer work is just a habit. The money I donated was not much, just a gesture. I wanted to do something within my ability. At that time, although the news said that experts had confirmed that the new coronavirus was definitely “human-to-human” transmission, I did not realize that the situation was much more serious than I had imagined.”

During the Spring Festival, workers returned home and factories stopped production, leading to a shortage of medical consumables. People in the WeChat group often asked for help, from donating sources of goods, transportation, finding doctors to assist in confirming product standards, and finally receiving them. Xiaoye actively and enthusiastically helped to find resources and connect information from all parties. Slowly, the scope of his work became deeper and wider. He said that buying goods was like going to war. Once the source of goods was confirmed, he had to immediately find reliable friends who could go to the site to inspect and pick up the goods, coordinate tense transportation resources, prepare funds, contact the receiving hospitals, and confirm the allocation quantity of each hospital from start to finish. For one order, he sat in front of his computer in his study for 12 hours to coordinate and plan, only drinking a sip of water and taking a bite of food. “Fortunately, my little buddies were very powerful, and we worked together to get things done.” Xiaoye seemed to be back in that situation, sighing heavily.

“If I hadn’t called the frontline nurses in the hospital to confirm the situation of receiving supplies, I wouldn’t have felt so deeply and angrily about what happened in Wuhan thousands of miles away. I remember it was evening, and there was no one on the large lawn outside the study window. I put down the phone and cried alone in the room with grief and anger.” Xiaoye then called the contact number on the official website of the Red Cross Society of Hubei Province to question the distribution of medical donation supplies. However, at that time, the website of the Red Cross Society of the province only published the total amount of donations received and the total value of supplies, without details of the supplies and distribution information.”

“I sternly questioned them about what supplies they had received, whether they had distributed masks and protective clothing to hospitals, and whether they knew that hospitals no longer had these supplies. The staff who answered the phone didn’t know anything, and their bureaucratic habits made me furious. Looking back now, the reason for my anger is also difficult to describe in words. Two sentences come to mind: ‘When the city gate is on fire, the fish in the moat are affected,’ and ‘When the rich feast in their mansions, the frozen bones of the poor lie on the road.’ Later, some people analyzed that it was a problem with the ability of government-run charity organizations, which may have some truth. But in that situation, I think it was caused by bureaucratic inertia. I have always supported accountability. But accountability is not the ultimate goal, it is to promote reflection through accountability, and to find and solve the root causes of problems. Now everyone talks about ‘normalizing epidemic prevention.’ I understand that ‘normalizing’ means learning from painful lessons and changing the way we work, communicate information, and provide feedback.”

JM curiously asked Xiaoye: “What did the nurse who answered the phone tell you?”

“Actually, she just told me in a very ordinary tone, ‘The hospital director doesn’t allow us to wear donated protective clothing, saying it doesn’t meet the hospital’s standards. Tomorrow, we may not even be allowed to bring masks.’ I was very surprised at the time and asked how they planned to protect themselves without masks. She still spoke in a calm tone and said, ‘I don’t know, several people in the neighboring department have already fallen ill.’”

“How did these words make you burst into tears?”

“This is like sending soldiers to the battlefield without giving them guns and bullets. You are urgently preparing supplies in the rear, striving to send them to the front line as soon as possible, but when you get there, you find that the front-line leaders do not allow their use. If you were in his shoes, you would feel the same sadness and indignation upon hearing such a thing.”

“What impact did this have on you?”

“My perspective on observing events has changed. At that time, I realized that most hospital managers were not on the front line of the fight against the epidemic, so they could ignore the situation of front-line medical staff and forget basic common sense, only following the original administrative management regulations and rules, and few had the ability to handle crisis events or take responsibility. Once people become machines of the system, they lose the ability to think. In this context, I was somewhat pessimistic about controlling the epidemic at that time, and when I thought about the subsequent impact on the economy, my sense of crisis became even deeper. Therefore, I am more actively involved in donating to public welfare actions on the front line of hospitals.”

“Do you have a sense of mission?”

“Not really. It’s just a sense of crisis – ‘there are no eggs under a toppled nest’.”

“Do your friends around you have the same thoughts and actions as you?”

“Not all of them. Some friends are very active like me, while others are indifferent. I asked a friend who went abroad for the New Year to find a local source of masks, but he told me not to cause trouble for the government and said, ‘China is so powerful, why do you need to donate any supplies?’ ” Xiao Ye replied with a smile.

We are just helping ourselves

It is important to note that medical supplies have strict standards. In order to prevent medical accidents, hospitals have their own procurement standards, strict inventory and distribution processes. Although individuals, legal persons or organizations within the country can all be recipients of donated epidemic prevention materials from overseas, there are two special regulations for donations to Wuhan, Hubei Province:

According to the announcement “Notice on Mobilizing Charitable Forces to Participate in the Prevention and Control of the New Coronavirus Pneumonia Epidemic in an Orderly Manner” issued by the Ministry of Civil Affairs on January 26, 2020, the materials collected by charitable organizations for epidemic prevention and control in Wuhan, Hubei Province can currently only be received by the Red Cross Society of Hubei Province, Hubei Charity Federation, Hubei Youth Development Foundation, Wuhan Charity Federation, and Wuhan Red Cross Society.

According to the content of the “Announcement to the Public by the Wuhan Red Cross Society (No. 6)” issued on January 30, 2020, if the donated materials to the Wuhan Red Cross Society are intended to be donated to a specific medical institution, the donor can directly send the donated materials to the recipient unit after confirming with the medical institution, and complete the donation procedures at the Wuhan Red Cross Society later with the proof of donation to the designated recipient unit.

Among all the recipients mentioned above, only the recipient with official background can enjoy the tax exemption policy for imported materials in accordance with the law. In addition, the Emergency Support Group of the Wuhan New Pneumonia Prevention and Control Command issued the “Announcement on Matters Related to the Purchase or Donation of Epidemic Prevention and Medical Consumables” on January 30, 2020, which detailed the standards and matters related to donated materials. Among them, there are the following regulations for products from overseas medical device manufacturers:

- Those who have obtained the qualification of registration certificate for imported medical equipment products within the country can purchase or donate;

- Those who have not obtained the registration certificate for imported medical equipment products within the country, but meet any of the “foreign standards” in the attachment and can provide the foreign medical device listing certificate and inspection report for the relevant products can purchase or donate, and the products can be directly sent to medical institutions for use after arrival;

- Those who have not obtained the registration certificate for imported medical equipment products within the country, but meet any of the “foreign standards” in the attachment, but cannot provide the foreign medical device listing certificate and inspection report, will be inspected by the emergency support team of the Wuhan New Pneumonia Prevention and Control Command at the site of the goods upon arrival, and if necessary, samples will be sent to inspection agencies for inspection of key indicators. Those that meet the requirements will be sent to medical institutions for use.

For materials that do not meet the above conditions, whether they are purchased or donated, they cannot be used as medical supplies. If there is a special need, the Wuhan City Market Supervision and Administration Bureau will send the product to a qualified inspection agency for inspection in accordance with the “domestic standards” in the attachment before it can be used.

Subsequent facts have shown that even with the tireless efforts of government officials and many local volunteers joining the front line work, there was still a significant shortage of manpower during that special period in Hubei and Wuhan, and the backlog of a huge amount of materials could lead to corruption loopholes. The emergency situation made it very difficult to implement policies effectively. The weighing of priorities and how to make trade-offs tested the wisdom of the implementers and decision-makers.

Xiaoye’s personality is like a fire, and he is also very passionate when it comes to doing things. With the evolution of the situation in Wuhan, Xiaoye’s emotions have been like a roller coaster. For a whole month, Xiaoye has also encountered various people who participated in public welfare actions online.

“Some people always say that our public welfare actions are helping Wuhan and Hubei, but I think this time is different from supporting Wenchuan at that time. We are helping ourselves – helping Wuhan compatriots and supporting frontline medical staff is suppressing the spread of the virus and protecting ourselves.” Xiaoye said. “supporting Wenchuan” that he mentioned refers to grassroots public welfare organizations’ aid action after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Some public welfare figures have called 2008 the “first year of civil public welfare”.”

With the government taking over factories and the National Ministry of Industry and Information Technology coordinating production, the phased mission of civil public welfare has also been completed. “I think this is normal. Civil public welfare is just a supplement to government social governance. The main reason is that institutions such as the Red Cross Society of Hubei Province and Wuhan have weak capabilities and are too inactive,” Xiaoye openly criticized official charitable organizations.

Xiaoye also knew that the donations they made at the time were just a drop in the bucket. JM also saw many individuals and temporary public welfare groups with various backgrounds who took spontaneous actions like them. At the beginning of the anti-epidemic period, they were the first to react and quickly donated urgently needed medical supplies to the front line of hospitals. Apart from JM, it seems that not many people paid attention to them, and there was no official or self-media to publicize and report on them.

Although there were many unsatisfactory aspects of the donation actions, many doctors were still very grateful for the warmth given by these anonymous individuals during the extraordinary period. Xiaoye still keeps many WeChat messages from Wuhan hospital staff in his mobile phone, although they only contain simple words of “thank you”. Although they have never met, recalling the days when they fought together, it feels like a spring breeze blowing over Xiaoye’s heart.

Xiaoye also criticized various phenomena in the anti-epidemic period, and recommended that I read a series of analytical articles written by economist Huasheng on this epidemic. Due to the length of this article, it is not convenient to list them one by one. A sixty-year-old acquaintance of Xiaoye said that he saw a trace of the May Fourth Youth’s passion in Xiaoye. Although it is only a trace, it is still precious. Although this trace of passion is not always easy to ignite in ordinary life, it is still a spark! JM also believes that there are many individuals like Xiaoye around us, and the trickle can gather into the sea, and the spring breeze and wildfire will also ignite.

(At the request of the interviewee, the names used in the article are pseudonyms.)

Picture: “Forty is not confused” (Handmade eternal flower custom product)

Design and production: Chen Feng | Photography: Yolanda Life Aesthetics Studio | Selling price 1500 yuan. Sold out)

Editor’s Note:

During the SARS period, Chai Jing, then a reporter from China Central Television, directly asked an official in an interview why information was concealed and whether it was due to systemic issues. Today, investigative journalists have either left the profession or been detained, and no one remains to personally pursue the truth on the front lines on behalf of the public or to fulfill the people’s right to oversight. Is this not a tragedy?

Should the Chinese people who have not experienced historical events learn from this lesson? Should they begin to reflect on what they have given up, and what legacy these concessions will leave for future generations? Are they and their descendants truly just cold, insignificant numbers in statistical reports?

Translated by ChatGPTm

Edited by Wind

Chen Ya | From ChatGPT to Creative Education

By Chen Ya, Jointing.Media, in Wuhan, 2023-02-24

Schwetzingen 2022

SQM, Jointing.Media

Recently, the online publication “Clarkesworld,” established in 2006, has announced the suspension of submissions without a clear timeline for resuming. The reason behind this decision is straightforward: many authors are employing AI technology to generate their literary works and then submitting them under their own names. This well-renowned magazine, which has been awarded the Hugo Award for Best Semiprozine thrice, has received over 500 unsatisfactory submissions in the last twenty days, accounting for about 38% of the total. Majority of these submissions have AI patterns and form distinct clusters. This has increased the editors’ workload significantly and disrupted the magazine’s regular operation.

The emergence of AI in generating articles, books, and even artwork challenges the assumption that AI cannot replicate human creativity. The rate at which this singularity is approaching seems to be faster than anticipated. In the near future, AI will undoubtedly displace certain jobs, resulting in a “crowding out effect” on particular industries. However, in the longer run, the disappearance of some tasks may coincide with the creation of novel positions.

At present, AI’s creative output is heavily reliant on databases derived from human history. However, when homogeneous works are manufactured on an industrial scale and treated as commodities, their value diminishes proportionally as the quantity increases. It is akin to the difference in worth between an original master’s painting and a photocopy or printed replica. Creativity stems from thought, and if creators intend to keep pace with industrial assembly lines, they must chart a new course. Original thinking is a personalized aspect of human nature that contrasts with batch-made AI products that cannot be quantified or replicated through data analytics at the moment.

Human beings typically acquire new skills by imitating, internalizing, and then mastering them through regular training. Conversely, AI “learns” skills through extensive data-driven training and eventually begins to replace the repetitive tasks performed by certain professionals or researchers. Only a select few individuals manage to break free from convention, innovate, and develop original skills after mastering the ones passed down to them by their predecessors – something that AI is yet to accomplish. Moving towards the age of collective intelligence, however, it is necessary to make significant advances in the field of neuroscience to unlock groundbreaking research findings in AI.

Machines appear to be “smarter” than humans due to their faster computational speed, which is in turn supported by the artificial hardware, software, and integrated systems behind them – at least for now, these systems are “artificial” and therefore theoretically subject to physical limitations. However, if brain-computer interface technology were to become more advanced, humans and AI may eventually operate on the same level of computing power, yielding an uncertain outcome.

Many literary works explore the possibility of AI evolving into a superior species to that of humans. Regarding this, the author chooses to maintain an open mindset. As AI continues to evolve, and if the human brain fails to keep pace, the science fiction narratives of this theme could ultimately become real. The law of the jungle, “survival of the fittest,” is a harsh reality.

Machines currently outperform humans in terms of physical ability, while the cognitive ability of AI remains a topic of scientific debate. However, it remains uncertain whether children will face real threats from AI. Although problem-solving skills can help children obtain access to higher education and prestigious schools, it is unclear if they can avoid being replaced by AI in the workplace. Hence, it is essential for parents to plan ahead for the future.

“Parents’ love for their children prompts them to plan for their long-term future.” In addition to the commonly mentioned cultivation of psychological resilience in the face of setbacks, the learning ability to adapt to changes, and the formation of positive habits for life and studies, how can parents guide their children towards a more creative and innovative lifestyle?

As Mr. Tao Xingzhi once put it, “Life is education.” By starting with daily life, children can cultivate the habit of finding multiple solutions to practical problems, and develop the ability to explore and learn new knowledge around those issues. However, all of this depends on high-quality companionship from parents. During the preschool and primary school years, parents can spend more time helping and supporting their children in discovering their true interests. Moreover, parents can inspire their children by continuing to learn and working hard towards their own interests, becoming a role model for their offspring. These practices are key components of family education.

Nurturing creativity in education calls for more than just time; a conducive space is also necessary. It is essential to create an educational environment that promotes innovation and sparks children’s imaginations both at home and at school, requiring a collaborative effort between parents and educators. Unfortunately, as soon as children enter junior high school, most of them are subject to immense pressure regarding high school entrance exams. Can excessive competition be averted? When parents and educators struggle to reach a consensus on educational values, parents must carefully weigh and make informed choices. Achieving a balance between these sometimes conflicting interests is critical.

Thinking, knowledge, and ability constitute the three integral components of creative education. According to psychology, creativity encompasses the ability to comprehend the essence and internal relationships of objective phenomena, and also to generate original and socially meaningful insights based on this understanding. Creative thinking represents a critical mode of thinking.

As stated in the book “Lifelong Kindergarten,” creativity is inherent in every person, and education must strive to help them unleash their full creative potential to adapt to an ever-evolving world. Only through creativity can children better face an uncertain future.

Author’s bio: Chen Ya, a person living in another world.

Translated by ChatGPTm

Edited by ChatGPT Next

Ralated:

Israel’s Green Pass Policy: A Chronicle of a Tragedy Foretold

【城市】| City

By Shirly Bar-Lev, in Israel, 2022-09-05

Escalation of Commitment refers to decision-makers’ tendency to persist with or even intensify losing courses of action (Sleesman, Lennard, McNamara, Conlon, 2018). In a typical escalation situation, large amounts of resources are initially invested, but despite these expenditures, the project is in danger of failing.

At this point, the decision-maker must decide whether to persist by incurring additional expenses or to abandon by terminating the project, or exploring alternative courses of action (Moser, Wolff, Kraft, 2013). Only at that point, the decision-maker is so invested in the project that he or she is pushed to aggravate the steps taken, and invest further resources.

Escalating commitment to a previous course of action not only traps the decision-makers but pushes them to behave in ways which act against their own self-interest, and that of the people they represent – sometimes with catastrophic consequences (Bazerman and Neale, 1992).

In a recent paper, Hafsi and Baba (2022) show how collective health fear, fed by politically fearful leadership, generated a cascading, isomorphic set of exaggerated responses in most countries. Muller (2021) similarly shows how the trap of what she names “performative scientism” has led to a decision-making process that is secretive, paternalistic and dismissive of dissenting views. This resulted in excessive reliance on, and confidence in, catastrophic projections that informed the enforcement of aggressive lockdown and vaccination policies regardless of their toll on public health and trust.

I argue that pursuing such a commitment bias was made possible by governments persuasively portraying the Corona outbreak as a “potential uncertainty” – one that no known possibility is sufficient to counter, and therefore requires a distinctive perspective on the future, and the present. Its uniqueness is so overwhelming that it warrants and legitimizes new forms of mass surveillance, detention, and restrictions (Samimian-Darash, 2013).